I was introduced to the film cradle of Iran almost five years ago. Most of the movies had a common thread, minimalist show off, no luxury with any kind of tricks, offbeat stories and very elegant narration. I was fascinated by their styles; saw a bunch of movies by

Makhmalbaf, Etemadi, Mehrzui, Majidi, Panahi, Karimi and

Mahranfar. They are very acclaimed and highly recommended film-makers across the globe by their sheer talents, but I personally have my deepest reverence and admiration to the master

Abbas Kiarostami, I must say he is the director’s director.

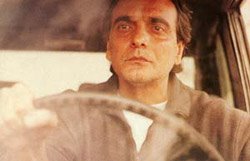

Taste of Cherry is a sublime mixture model of a fairy tale told in the simplest spirit but surrounds a complicated tug-of-war between the concepts of life and death. The way this film handles brilliantly the complex conflicts between suicide and life after, is I believe extraterrestrial to both western and eastern civilized worlds. A man, Badii

(Homayoun Ershadi) is driving through the city of Tehran and traversing a winding dart road for an unknown destination. Often, desperately he pauses in the road, asks the common men to help him out form something. The story takes a while before revealing. The camera always focuses on Badii, we see his tensed frantic expression, and we surmise that he is time-bound by some distressed task. Often we see the barren lands; the dust of the roads has eaten up the greens, we are sporadically interrupted by squadrons of military troops marching up the hill performing drills.

In this strange journey Badii meets with different people on road (for detail check out IMDB), someone is from a construction site, a young soldier (who outwardly intimidated by Badii’s inquiries and reveals his apprehension that he is talking to a psycho), a safety-guard in a cement-making site, a seminarist, a Turk who works in the natural science museum as a taxidermist and so on. Badii persistently explains his predicament and seeks help from them. He is a desperate man who is actually bent on committing suicide and looking for someone to ensure at next day dawn that he is buried, dead and not alive. He is earnestly pleading for a compassionate person who will come back at six in the next morning near an isolated spot in the infertile land (a little off the road and a hole down a slope) and will throw twenty shovelfuls of dirt over his body, which will be lying in that hole! Then the person can take a hefty amount of money (which will be left at the site) and can go away.

Master auteur

Kiarostami gripped this commotion perfectly. Any normal individual will behave exactly similar against Badii, as the movie portrays. Still we see there are few fundamental differences in the outlook of diversed age group. We see when Badii accosting the young soldier, he is increasingly suspicious about Badii, judging him as a madman. But the elder taxidermist or the seminarist take a different angle, they try to comprehend and sympathized to the situation more deeply and remind Badii about the Koran prohibitions, the embargo that one must not kill himself. The taxidermist also alerts Badii about his personal experience, once he was decided to commit suicide but being in a mulberry orchard, he tasted one, and the taste propounded his wish to live. He evaluated the taste of cherry with the metaphor of constructive surface of life.

In the closing stages of the movie we see at late night (or early morning) in a thunderstorm; Dabii leaves his home for his burial place. However, we don’t see actually what Badii did at his home (we see from a distance through the window that he did something, we surmise that he has taken his sleeping pill, as mentioned earlier in the movie). He drives his Rover to the hill, near the hole down the slope. Interrupted by frequent lightning we see Badii’s face, his eyes are open. They progressively go half-close, then open and close. We hear intermittent thunder sound, rainfall; occasional blacks on the screen, Badii’s face and then the screen go permanently black.

and the movie is still not over...

Well, next comes the most absorbing or intricate part of the film. We see the landscape in natural light; we see the actual shooting is taking place. We see

Kiarostami, his crew and Badii too, in a different dress beside the hilly area offering a cigarette to the director. The cameraman appears,

Kiarostami directs with his walkie-talkie to a distant military troop. The military take a rest beside a cherry tree. The film is now over.

No matter, how many times I swear by

Taste of Cherry, I am still uncertain and hesitant about the ending. What I discover from the movie that Kiarostami addressed two vital issues here,

a) is regarding the concept of suicide and

b) about the dissimilar worlds of death and life after. From the side of Badii we witness Badii’s point, he is unhappy and want to be free from pain. Though Koran forbids the dictionary term “suicide” but Badii tries to clarify that being unhappy is much sinner because it also hurts those near him! So, God should have a proper reason, to free Badii from the pain. This is a very complex message.

Kiarostami gives high respect to the viewers and may be that’s why he is unspoken and leaves the judgment (whether Badii is right or wrong) to us. About, the last few minutes my clues are pretty less I must say.

Kiarostami demonstrated two different countenances of our worlds, one, with Badii’s death and other with the present tense. The man, Badii is still living and dissimilar as we see him in the movie. We see the squadron beside the cherry tree,

Kiarostami suggested that with a single suicide or not (well, we are not sure if Badii actually died or not!), there is really no change in the society (often we see in the movie, there is an implicit hookups with the political currents of Iran).

Kiarostami never dictates the audience (though many a great directors do!) with his political curvatures or with shining glow of social messages. His films bear the utmost admiration to the individuals, to the verdict of us. That’s why his films are always haunting, more haunting in the end scenes (remember

through the olive trees or

the wind will carry us) as they tickle with the viewers, the viewers have to take the decisions with their individuality.

Kiarostami proposes a resemblance of a rebirth through the ending of

Taste of Cherry. A distinct western trumpet sound, the soldiers have stopped drilling. The audiences have to rise up from their sits (like Badii woke up from the hole of distress and now with his rebirth among us) and explain for the movie.

Ta'm e guilass (Taste of Cherry - 1997)

Directed By: Abbas Kiarostami

A woman is a woman is a sandwich venture of Godard between his breathtaking debut in A bout de soufflé (Breathless) and the tragic classic Vivra Se Vie (My life to live) and I still wonder how all these three are different in all aspects. Godard was always uninhibited, lighthearted, and purposefully slapdash in style (as Ray commented once) but was a true experimental mind. He mastered the true sense of being wild in movie, and his intellects, playfulness with the audience and the characters are always worth mentioning.

A woman is a woman is a sandwich venture of Godard between his breathtaking debut in A bout de soufflé (Breathless) and the tragic classic Vivra Se Vie (My life to live) and I still wonder how all these three are different in all aspects. Godard was always uninhibited, lighthearted, and purposefully slapdash in style (as Ray commented once) but was a true experimental mind. He mastered the true sense of being wild in movie, and his intellects, playfulness with the audience and the characters are always worth mentioning.