the Morning Comforts

La Notte is the sophomore effort of the proverbial

La Notte is the sophomore effort of the proverbialtrilogy (L’ Avventura, La Notte and L’ Eclisse) crafted by Antonioni. Though the trilogy essentially not having a pet name resembling the memorable “Apu-trilogy” or so, but all three are connected in a same string of troubled relationship set in the lyrically stunning architectural backgrounds, whether beautiful immense nature or pleasant glamorized 60’s urban Italy.

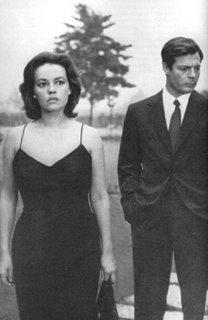

La Notte has a little plot to speak of. Antonioni follows Lidia (Jeanne Moreau, more celebrated in portraying the role of Catherina in Truffaut’s surrealistic masterpiece Jules et Jim) and her husband, the renowned author Giovanni (Mastroianni) in a course of a single day and night. They visit their friend Tommaso who is dying in the hospital. They wander the busy streets of Milan, attend promotional party of Giovanni’s latest book, visit clubs and attend one more party organized by a rich millionaire in night and finally they confront the cold apathy that has expanded among them. Both rebuff any sexual advances of the unknown, but they perform so only out of obligatory respects. In the next day, at dawn Lidia and Giovanni separate themselves from the crowd of barmy party-goers and make their way down a large empty field of a golf course.

They discuss their marriage in equal doses of resentment, and denial, but finally admit that their love has atrophied. Lydia accuses Giovanni for the emaciated affection but he becomes emotional, perhaps the confrontation forces him to suddenly feel a tinge fondness towards her, somehow. In a fit of passion he lunges toward her while she whispers in the screen that she wants to hear that he does not love her. Antonioni frames the vast emptiness of the field and leaves the audience in with little hope for comfort to predict their future.

The minimalist usage of symbols in Antonioni’s ventures is too commendable. From the very beginning he captures vast architectural buildings of Milan, the high rise, the chemistry of geometrical figures. This is much different from L’ Avventura yet we find a similarity in capturing large architectures as backgrounds. Antonioni repeatedly composes Lidia from different angles and communicates with the viewer. She is leaning toward walls with her vacuous interaction with life; she is walking no-direction-home or stares out from the hospital window to watch a sudden glimpse of a helicopter thus alienating her composition from her surroundings. With a microscopic detailing we see Lidia stands alone wherever and throughout the remainder of the film.

Few shots I should point out before I pause. After the millionaire throws the offer to Giovanni for a permanent job in his organization we follow the raucous party guests with a short spell framing an aviary and a bird. We recall the whole setup of the evening party and we see that numerous instances of creating patterns of vertical strong lines or series of horizontal blocks with shadows. Antonioni counter balances his compositions with these hurdles between withered relations in the premonition of a new industrial Italy.

La Notte is another aesthetically complex but critically stimulating movie.

La Notte (The Night -1961)

Directed By: Michelangelo Antonioni